How the Blueprint Works for Revision

Our Summer Blueprint Sprint is not just for writers working on new ideas. It's effective for writers working on revision, too. This post explains why and shows you how.

#AmWriting is a reader-supported publication. To join the Blueprint Summer Sprint, become a paid subscriber.

This is the last in a series of posts about the #amwriting Summer Blueprint Sprint. If you missed the previous posts, they are here:

Full disclosure: this is a writer-focused version of a piece I shared on my own Substack yesterday.

All the prep we’ve been doing for the #amwriting Summer Blueprint Sprint has got me thinking about when it’s effective to step back and take a big-picture view of a book project versus zooming in to focus line-by-line on the story or the argument— and there are three primary moments:

At the start of a project. Sometimes a writer is so inspired that they go straight to the page to capture the spark of the idea, start writing, keep writing, and produce a book that is cohesive, whole, and beautiful. May we all experience that sort of powerful flow in our creative lives! But the start of a project is usually a lot more fraught, filled with stops and starts. I believe it’s a critical moment to pause and consider the fundamental questions of the project. Why are you writing it? What’s your point? Who’s your ideal reader? Even a short period of inquiry at the start of a project can have a profound impact on the resulting book. This is the process my Blueprint method is designed to facilitate for fiction, nonfiction, and memoir.

When the writer is stuck. Another good time to pause and look at the big picture is when a writer can’t move forward. Maybe they’ve written three chapters or five or thirteen, but they don’t know what comes next. Or they know that what they’ve written isn’t holding together. Or there is too big a gap between their skill and their taste. (See the Ira Glass quote on this gap — James Clear has an interesting write-up on it.) This is another good moment to answer those big questions. Clarity about intention and structure usually solves the problem of being stuck.

Before a writer undertakes a revision. This is another moment when writers could benefit enormously from stepping back to look at the big picture of their manuscript, but most of the time, they plow ahead without giving their revision a strategic thought. The way they plow is to go right back to Page 1, following the same grooves they followed as they wrote. By grooves, I’m thinking here about ruts in a road. Maybe a covered wagon whose wheels follow along the same track the wagon ahead of them took. It’s really hard to steer out of those grooves but relatively easy to just keep going, reading chronologically with the same mindset you had when you wrote the draft. There is a better way—and that’s what I want to share with you now.

The Problem With Starting a Revision On Page 1

We’ve all done it — finished a draft and sensed “the end” the way a racehorse senses the finish line. We think, This draft is amazing! It just needs a little tweaking! Perhaps I can get it to our beta readers/production team/agent/editor ahead of my deadline! Maybe I am secretly brilliant and not subject to the realities of writing that drag other writers down!

We head to Page 1 and get in those grooves. If what we see is pretty good, we cruise along on the surface of our manuscript thinking, Yup, that chapter’s good. Ohh this passage is great. Love this bit of dialogue. Look at me! We may change a word or two here and there, tighten up the language, and fuss with the flow, but we’re really just keeping our eyes glued to the page and our minds in the rut of what we’ve already created.

The result of this kind of revision is often a manuscript plagued with problems and a writer closed off to hearing honest feedback about what is working and what is not.

If we get into the revision groove and what is on the page is a mess in some fundamental way, we may start to think, Uh oh — this doesn’t make sense. Wait — why did I put that thought there? OMG — am I going to have to rewrite that chapter again??

And then the voices of doubt and despair rise up: I’ll never finish this book. Good thing I became a lawyer/doctor/textbook editor/organic farmer because I can’t write to save my life. My dad was right — I’ll never make anything of myself without a PhD. (Note: this was my dad…)

We quickly get overwhelmed by everything we have to do to take our pages from rough to viable, let alone to get them to great. And what happens next?

We might put the manuscript in a folder on our desk where it never sees the light of day.

Or we might hand over our pages to a beta reader or a professional to get an opinion on what’s working and what’s not. That act of handing over can be problematic if we’re also handing over our power. We may be saying to ourselves, I don’t know what’s wrong and I can’t figure it out: you tell me! This sets you up to swallow whole whatever feedback is offered, whether it is useful or not, or effective or not, or resonant or not.

There is obviously enormous value in having other people read and comment on our work — especially professionals; this idea is the basis of my entire career as someone who trains and certifies book coaches, and I have nothing but the utmost respect for compassionate and skilled editors — but how we hand our work over is critically important. We need to do it at the right time, and select the right readers, and approach them with the right mindset — which means bringing a spirit of collaboration and inquiry rather than a spirit of fix it for me.

While the feedback you get from a manuscript review is likely insightful and useful, you still have to wade through it, figure out what to make of it, figure out how to prioritize it, and figure out how to execute it.

The result is very often that you end up just as overwhelmed as you were before you sought help. You still dread the work of revision. You slog through it joylessly, complaining to your writer friends that you are in revision hell.

There Is A Better Way

There is a better way to approach the revision process and that is to step back and look at the big picture before you turn to the pages.

This means not starting at Page 1.

This means not reading straight through the manuscript chronologically.

This means not handing over your pages to someone else (yet.)

This means that you start the process by thinking strategically.

How Do You Think Strategically About Revision? Enter the Blueprint*

Although I made the Blueprint to help writers start a book from scratch, the way I most often use it in my own book coaching is to help writers who are revising a manuscript.

It provides a tool and a process for thinking strategically and ensures that both the writer and coach pay attention to what matters most.

*Important note! Obviously, anyone can use my Blueprint method — I wrote three books about it. And we’re running a whole summer program on it here at the #amwriting podcast that we hope you will join. But only Author Accelerator Certified Coaches are authorized to teach it publicly in workshops, conferences, and online venues, and to publicly advertise Blueprint coaching services. If you are interested in our certification program, go to bookcoaches.com/abc

Here’s how Blueprint for revision works works:

The writer takes a week or two to work through the 14 Blueprint steps. (In the #amwriting Blueprint Summer Sprint, we’re taking ten weeks — so you’ll have plenty of time to let it all sink in.)

They write down why they are writing this book, who it is intended for, what point they are hoping to make, or what experience they are hoping their reader will have.

They write book jacket copy and a super simple version of the plot (fiction/memoir) or the TOC (nonfiction). They consider their title and ask key questions about structure.

They put the major elements of the story or idea into an outline — but not an exhaustive one with every single story beat or every single argument they are making in the book. In order to be effective, the outline must be extremely short — no more than 3 pages — so that you can see the shape and flow of it, and it must focus on the biggest problems that are likely to show up in that genre or category of book.

I know I sound bossy here; it’s just that this outline serves a very specific purpose: to allow us to see the story or the argument. You need to be able to examine it, stress test it, turn it over, and look at all sides of it, and the only way you can do that is if it is concise.

The answers to the 14 Blueprint questions and these specific kinds of outlines (called The Inside Outline for fiction; the Outcome Outline for nonfiction; and the Impact Outline for memoir) form the basis of the strategic assessment you will be doing of your manuscript.

Doing this assessment before you hand over your manuscript to readers or editors for review yields profound insights. Is it easy to answer these 14 questions? Odds are good that means you’ve got a solid manuscript. Do you struggle with the most fundamental aspects of what you’ve written? That’s probably pointing to the places where the manuscript needs work.

The Blueprint invites the writer into a process that is a different process from the writing process. Instead of looking at the words on the page, you are asking yourself, Where does this work align with my intention and where do I think there is still work to be done?

You know more than you think you do.

Sometimes a writer will realize during the Blueprint process that they have not written the book they really wanted to write. Other times, they will correctly identify that the first half of the book is great but the second half is not (or vice versa.) They often know if the book is too short or too long or if it veers off in a direction that doesn’t work. They often identify parts of the work they love and that they want to bring to the forefront in the revision.

If you give yourself the time and space to honestly assess your work — including identifying where that work shines — you are taking ownership of your revision. You are helping build your confidence as a writer. You are teaching yourself how to find your voice. You are also setting yourself to get much more nuanced feedback from your beta readers or editors. There is so much goodness in this process!

Revision is primarily a strategic undertaking, but most people don't approach it that way. The Blueprint gives you a process for making strategy a priority.

At the end of the Blueprint Summer Sprint, we will be sharing with you a list of Author Accelerator Certified Book Coaches who are offering specials for #amwriting podcast listeners. If you would like a review of your Blueprint (and you are not the writer who wins the grand prize), you can consider whether that is something you think might help. You also have a chance to get to know our four Coach Hosts in the AMAs and write-alongs we’ll be offering, and perhaps one of them will be a good fit for providing a review. The back-and-forth discussion around the Blueprint is usually fantastically productive —and much cheaper than a full manuscript review.

What Do You Do With the Information You Uncover By Doing the Blueprint?

You might go in and surgically repair something that appears throughout the manuscript like a thread in a tapestry.

You might work on only the first three chapters or only the last three.

You might add or subtract or fix a certain POV.

You might work on a subplot or a particular concept — again, tracing that element of the book throughout the manuscript rather than coming across it intermittently during a chronological read.

If what needs help is something around voice — in nonfiction, for example, if a journalist or a lawyer is too fact-based in their writing, or an academic writer is too reliant on citing other thinkers rather than embracing their own authority — you can work on voice. You might revise one or two chapters, working on finding the language and rhythm that is uniquely yours.

Working through the Blueprint allows you to work on the part of the manuscript that needs the most work.

My Revision Philosophy

In a nutshell, my philosophy on revision is the same as my philosophy on writing in general:

Think before you write.

The novelist Jorge Luis Borges said that “art is fire plus algebra.”

We all know what the fire feels like — the spark of the idea, the flash of the story we must tell, the wisdom we are passionate about sharing with readers, the deep yearning and ambition that keeps us sitting down and putting words on the page with the belief that we can move our someday readers.

But most of us need the algebra to make it all work. We need the intention, the strategy, the prioritizing — and there is nowhere in the creative process that is more true than with revision.

Join the Blueprint for a Book Summer Sprint and Work On Your Revision

The Blueprint for a Book Summer Sprint starts July 2. To play along, you must be a paid subscriber.

To join the Blueprint Summer Sprint, become a paid subscriber.

Subscribed

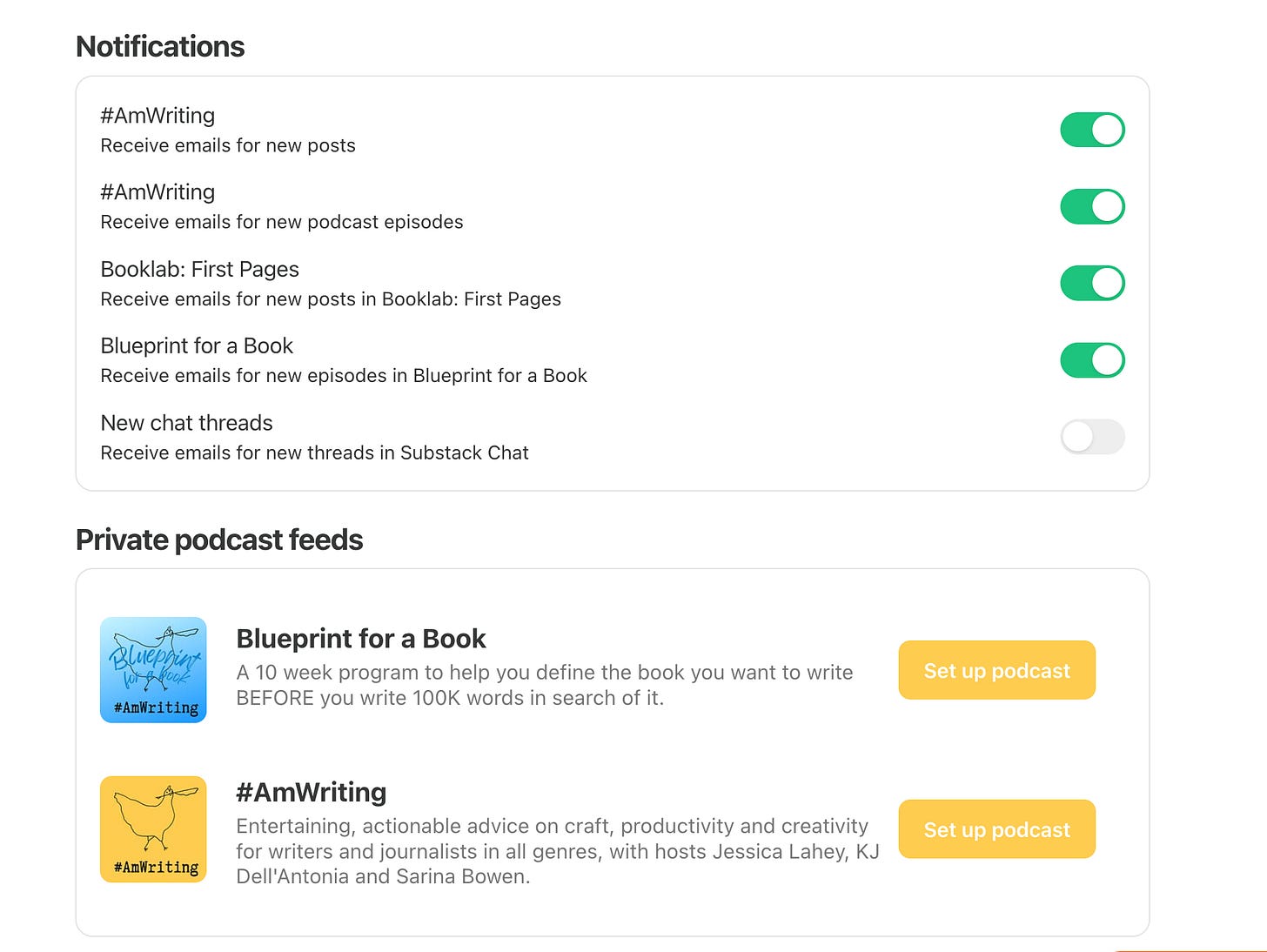

Once you sign up as a paid subscriber, you can set up your podcast feed. Don’t worry, it’s simple! Click here to go to your #AmWriting account, and when you see this screen, do two things:

Toggle “Blueprint for a Book” from “off” (grey) to “on” (green).

Click “set up podcast” next to Blueprint for a Book and follow the easy instructions.

Once you set those things up, you’ll get all the future Blueprint emails and podcasts (and if you’re joining the party a bit late, just head to our website and click on Blueprint for a Book in the top menu).

Using this method now!

I am currently drafting the manuscript of the nonfiction book I started planning during the last summer Blueprint challenge (was that 2022?). I have four draft chapters due tomorrow (!) to my editor for some feedback on tone, structure within chapters, etc. It's interesting to go back and see what has and hasn't changed from the original conception of this project.

I don’t think I’m receiving the emails. Early in I made sure that the toggles were “on”. Any suggestions?